After a wonderful night of dancing at the royal ball, Cinderella – in the exquisite dress given to her by her fairy godmother – looks at the clock and notices to her great dismay that it is already almost 12 o’clock. Afraid of being too late and being unmasked as an intruder to the high society assembled for the occasion, she panics, starts running and loses her slipper.

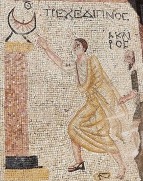

The ancient mosaic shown here reminds the viewer of this story. It portrays a nicely dressed party-goer looking at the clock (an ancient model, namely a sundial). The person realizes it is getting late and starts to run, losing a slipper in the process. This mosaic was made in the third or fourth century CE in Antioch in Syria (modern-day Antakya, Turkey), one of the largest cities of the ancient Mediterranean. Next to the similarities there are also some major differences with the fairy tale. The protagonist of the mosaic is male and the time on the clock is not midnight – a sundial is in fact useless at night– but the ninth hour of the day (the symbol Θ above the clock is the Greek numeral 9). Greco-Roman hours are not easy to convert exactly, because the duration of daylight was always divided into 12 hours, on short winter days as well as during long summer days. In any case, since the count started at sunrise, the ninth hour is always in the (later) afternoon.

The protagonist on the mosaic is, moreover, not running away from a party, but heading to one. The Greek letters ΤΡΕΧΕΔΙΠΝΟΣ (trechedipnos) explain that he is a man running (trecho) to dinner (deipnon). There are many ancient texts, and a few more mosaics just like this one, confirming that the ninth hour was indeed the normal time for the start of dinner parties. There are even ancient invitation cards on papyrus confirming this. But, of course, not everyone ate their dinner in the middle of the afternoon. The average farmer or artisan would still be at work: in winter, when days were short, workers were still taking advantage of the natural light, and at summer the scorching midday heat was just receding, making working conditions ideal again. So, what we have here is the dinner time for special occasions and for the leisured classes who could afford to have lazy dinners every day of the year.

Despite all these differences, a comparison between the mosaic scene and the famous fairy tale works when we interpret both events in terms of social anxieties. Cinderella is anxious not to leave the ball too late, for she knows that when the magic wears off, she will show her real situation in life, namely that she is an impoverished orphan who would not be accepted by the high society assembled in the palace. Our anonymous party-goer likewise dreads to be late. The old figure behind him is labeled on the mosaic as ΑΚΑΙΡΟΣ (akairos means ‘ill-timed’) and is therefore a personification of bad timing. This gives the otherwise amusing scene a dark undertone – which is reinforced by the fact that the symbol Θ is, besides the numeral 9, also an abbreviation of the word ‘death’ (thanatos). The fear of being late was also a social anxiety in the Roman empire: only poor people needed to work and would not be available in the middle of the afternoon. A well-integrated member of the elite had all the leisure in the world, had internalized elite temporal norms and hence always arrived on time. One of the stock characters from Greek comedy is the so-called parasite, a flatterer who tries to get introduced into elite circles well-above his own station to get free meals. But to get accepted into these circles and to get these free meals, he does need to come on time. Arriving too late at a dinner party means running the risk of being seen as a parvenu, and our Roman-day Cinderella does not want to run that risk!

Sofie Remijsen