Experiences of teaching Dutch primary school children about time and going to school in the Roman world

What was it like to be a Roman schoolchild? A few months ago, the project team designed an interactive tutorial about the life of Roman schoolboy and the ways of knowing time in the Roman world for school children aged 9-12. From June one, we (research assistant Kevin Hoogeveen and student assistant Hugo Oostdijk) have practiced and perfected the tutorial in primary schools in Bussum, Amstelveen and Rotterdam. In this blogpost, we share our experiences.

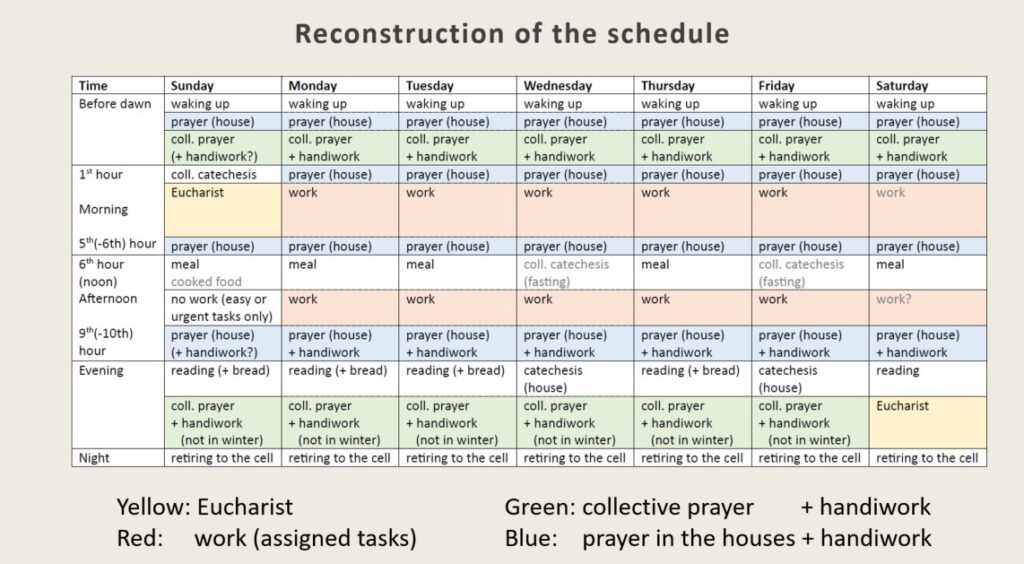

The goal of the lesson was to teach children about the ways in which Romans used and experienced time. A child’s morning routine and school day served as an example. We hoped that, by the end of the class, children knew more about:

1. how Romans measured time;

2. how the rhythm of people differed depending on their place in society (wealth, class, gender, being enslaved, etc.); and

3. inequality in the Roman world in general. Many children did not go to school at all, people could be enslaved and women were considered inferior to men.

For each school group, we started off with a small introduction into the Roman world with a lot of input from the children themselves. Caesar and Cleopatra were the best-known celebrities. Some were even familiar with the concept of Roman imperialism. Pointing out the fact that the Roman empire included modern-day Turkey and large parts of North Africa, and stretched all the way to Britain and Rumania, visibly fostered a sense of involvement and enhanced engagement in classes with a relatively diverse demographic.

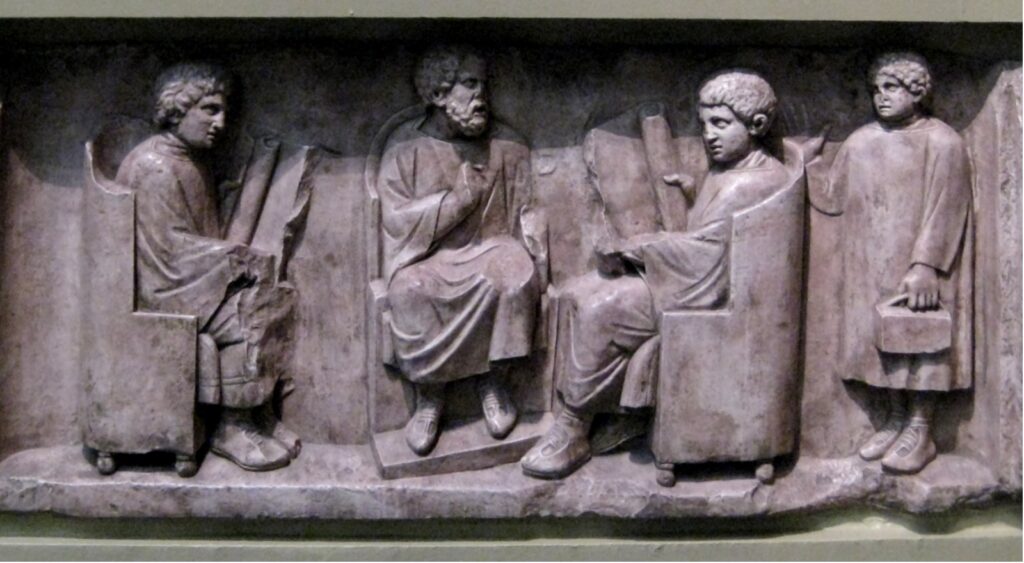

Next, we turned our attention to a fourth-century colloquium text which describes the day of a Roman schoolboy, from the moment he gets up until the end of his school day when the teacher accidentally sends the children home early, in the conviction that the next day was going to be holiday. The text was originally designed for children who were practicing the colloquial use of Latin and Greek. Because it is written from the point of view of the child itself, it is easy for children to relate to the Roman schoolchild and compare their day with his.

The children also acted out the colloquium texts. This created an opportunity to discuss the questions related to the text that the children answered earlier, but the little plays wre above all a fun way for them to reflect better on what happened in the story and also on how the lives of characters in the text had different rhythms.

In two more practical blocks of the class, the children learnt how to make a rudimentary sundial. We took them outside to see how the gnomon’s shadow moved throughout the day like that of a modern clock.

Hugo: “I had no prior experience with teaching in any way, let alone groups of young children. I learned a lot throughout so this project was probably more educational for me than for any of the children we encountered, but I really liked to try to enthuse children for the discipline that we all feel so enthusiastic about. Aside from the general challenges of getting some of the children to listen and actively partake (the intensity of which also differed per school) the try-outs of the lesson presented us with an opportunity to run into some more specific challenges that allowed us to finetune the end product. A great example is the sundial experiment for which we planned to go outside until we had to teach a class in the pouring rain, which forced us to come up with an alternative approach for those (many) days that it rains in the Netherlands.

The most challenging aspect however, was the fact that we were developing this lesson in a way that it could be taught by a primary school teacher, and they usually don’t have such an extensive knowledge of the Roman world as people working in the ancient history department of a university. It felt nice but problematic at the same time when teachers after class complemented us on how we could answer the questions of children about a plethora of different subjects concerning the Roman world, because this is exactly what a normal teacher would not be able to do. By writing an introduction document for the teacher and an extensive step by step plan of the lesson we hope to have overcome this challenge as much as possible and I think the end product has turned out to be indeed both accessible as well as educational.”

Kevin: “Until now, I had only been a teacher at Sunday school. Teaching Roman history to children at this young age was a whole new experience to me. I thoroughly enjoyed their enthusiasm and found joy in stating that the history of the Roman empire is a shared history of many people of diverse backgrounds. The sundial demonstration proved to be most interesting element of the class, followed by the short plays with the colloquium text as script. I hope Hugo, I and the rest of the project team will prove to have been able to share our knowledge with as diverse a public as possible by developing a class suitable for use in all primary schools.”

Kevin Hoogeveen and Hugo Oostdijk

The teaching material (in Dutch) is found here.