For those interested in the origin of monastic routines, Bentley Layton’s book The Canons of Our Fathers: Monastic Rules of Shenoute (Oxford, 2014) is highly recommended. It presents the first edition of a very early collection of monastic rules written in Coptic, 595 entries in total. These rules were not transmitted as a group, but abbot Shenoute of Atripe (ca. 347-465) and his successor Besa quoted them in their writings, and Layton carefully collected these quotes.

In ca. 385, Shenoute, the most prolific author in Coptic in late antiquity, became the supreme leader of a monastic federation on the west bank of the Nile, at the edge of the desert near the ancient village of Atripe and the modern city of Sohag [see the YMAP-South map]. According to Layton, the federation was founded when Pcol, the founder of a monastery (in ca. 360), and Pshoi, the leader of an eremitic community that transformed into a monastery, decided to link their congregations. Pcol, who also founded a third monastery for women in the village of Atripe, became the first archimandrite (superior abbot) of all three congregations and male and female ascetics associated with them, while remaining the abbot of the main monastery. His successor Ebonh combined the two offices as well, but Shenoute, who lived as a hermit after leaving the main monastery, only succeeded Ebonh as archimandrite of the federation, while two abbots and an abbess directed the monasteries. In the course of time, the communities have been referred to by various names:

- The central monastery for men was later called the Monastery of St Shenoute, but is best known by its modern name, the ‘White Monastery’, as the monumental church was built of white limestone. The church is still in use today.

- Similarly, the northern monastery for men is officially named the Monastery of St Pshoi, but often called the ‘Red Monastery’, on account of the red limestone used in the church building. The church is still in use today and admired for its polychrome decoration.

- Themonastery in the village, a cloistered community for women, no longer exists today, but has been excavated by Yale University.

These communities could include small children and youths, who participated in the daily monastic routine as much as possible like the adults. Each monastery comprised an unspecified number of houses, where monks or nuns slept and attended communal activities, including prayer and handwork sessions and instructional meetings.

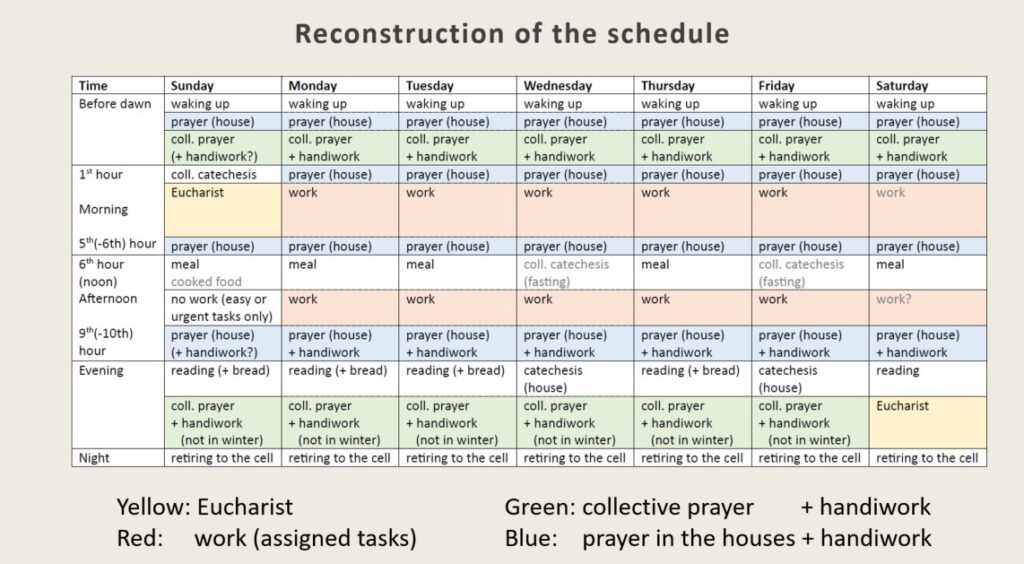

In his nine-volume work called Canons, which is largely preserved and meticulously reconstructed, and in some fragmentary writings, Shenoute quoted monastic rules (nos. 1-581) written by himself or by Pcol. The latter also appears to have revised and supplemented the rules of Pachomius (ca. 292-347), who was the first monastic leader to define monastic rules (from 329 onward). Just as Shenoute added new rules in the course of time in response to practical situations, his successor Besa discussed a number of supplementary rules in two of his works (nos. 582-595). These rules do not discuss the weekly and daily schedules systematically – as these were self-evident to the monks, the most basic routines are least likely to be preserved. But all the information together does enable us to get a detailed impression of the routines in the monastic federation (see the table).

In each monastery the Eucharist was celebrated twice a week, on Saturday evening and Sunday morning. Both services were mandatory, unless someone was seriously ill or instructed to stay behind. After the Saturday mass, the monks and nuns went to sleep and got up hours before dawn for the collective prayer. During the winter, when the hours were shorter than in summer, the time to get up was 3 hours before sunrise, to ensure that the siblings recited 51 prayer units. Children attended the collective prayer as well, but they were allowed to sleep during the event. At dawn, the superiors of the three monasteries gave catechesis, after which the Eucharist took place early in the morning. During the rest of Sunday, nobody was allowed to do difficult tasks, and only easy or urgent tasks were acceptable.

On other days than Sunday, the monks and nuns got up 1,5-2 hours before sunrise. The daily prayer schedule consisted of collective prayer before dawn and in the evening, either in the churches or other communal spaces, and prayer sessions in the houses: after waking up (not noted by Layton, but implied in rule no. 169), at the first hour (dawn), at the fifth hour or the sixth (noon) at the latest, and at the ninth hour (ca. 3 PM) or the tenth at the latest. During the collective meetings, the monks and nuns usually prayed twelve rounds, while being engaged in handiwork: the monks plaited reeds, the nuns worked with wool. However, during the colder months, they prayed six rounds in the evening and did not have to work, out of concern for those who were tired of fasting or working outside, so that they could eat their bread in peace. The prayer sessions in the houses included 18 units, or 24 units in summer. Layton previously thought that they were occasions for handiwork as well, but later indicated that this was perhaps not the case (compare Layton 2007 and 2014, p. 72).

Each change of activity was signaled by the striking of wooden instruments. Except on Sunday, the monks and nuns worked in the morning and afternoon. The daily meal was normally served in the refectory at noon (once a week it was cooked), and extra bread was distributed for those who needed to eat in the evening, which they could do in private at the time for reading. The rules do not clarify whether the daily meal was postponed to the evening on the two fast days, i.e. Wednesday and Friday, and at which moment of these days the superiors of each monastery and the house leaders gave catechesis.

Reading Layton’s edition of the rules and combining details scattered throughout the collection strongly improved my understanding of how daily life in the monastic federation was organized, especially with regard to the moments reserved for prayer, work or a combination of both. As disciplined life in the cenobitic communities may have been, especially in view Shenoute’s reputation as a very strict monastic leader, the rules show room for variation depending on the season and moderation for the sake of child monks, the weary, and the sick.

Renate Dekker

Further reading

On the rules

Layton, B. 2007, ‘Rules, Patterns, and the Exercise of Power in Shenoute’s Monastery: The Problem of World Replacement and Identity Maintenance’, Journal of Early Christian Studies 15.1, 45-73 [on the organization of space, time and offices in the monastic federation].

Layton, B. 2014, The Canons of Our Fathers: Monastic Rules of Shenoute, Oxford: Oxford University Press [edition of the preserved monastic canons compiled by Shenoute].

On Shenoute

Behlmer, H. 2022, ‘Shenoute: Update’, Claremont Coptic Encyclopedia, available online at https://ccdl.claremont.edu/digital/collection/cce/id/2178/rec/1.

Bell, D.N. 1983, The Life of Shenoute, by Besa, Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications.

Brakke, D., and A. Crislip 2015, Selected Discourses of Shenoute The Great: Community, Theology, and Social Conflict in Late Antique Egypt, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gabra, G., and H.N. Takla (eds) 2008, Christianity and Monasticism in Upper Egypt, vol. 1: Akhmim and Sohag, Cairo: AUC Press [on Shenoute and the monastic federation].

On the monasteries

Bolman, E.S. 2016, The Red Monastery Church: Beauty and Asceticism in Upper Egypt, New Haven–London: Yale University Press [on the church decoration in the ‘northern monastery’].

CCP Staff 2020, ‘’Elizabeth Bolman Interview: The Red Monastery Church. A Multi-Decade Project Brings a 5th C. Coptic Church in Egypt back to Vivid Life, Cultural Property News, available at https://culturalpropertynews.org/elizabeth-s-bolman-interview-the-red-monastery-church/.

Yale Monastic Archaeological Project South (YMAP-South), ‘The History and Goals of the Project’, available online at Yale Egyptology, with links to the sub projects ‘Shenoute and the History of the Monastic Federation’, ‘The White Monastery’, and ‘The Women’s Monastery near Atripe’.