In every society there are communal feasts, when most people are free from work and schools are closed. Here in the Netherlands, there has been some discussion lately concerning the inclusiveness of these feast days. Why should feasts with a Christian origin, such as Pentecost or even Christmas, be nationwide holidays for everyone, including people without a connection to Christianity? This situation means that people with a different cultural or religious background, are forced to take up vacation days for their (non-Christian) feasts. This is something people with a Christian background, however distant, do not have to do, whether they are religious or not. Some companies are now offering all of their employees extra days off instead of the fixed days, enabling people to schedule their own holidays. In that way, everyone is able to shape their own festival calendar.

In Roman Egypt a similar arrangement seems to have existed. Some people could choose for themselves which days to take off work for festivals. This was only the case for free, relatively wealthy people, like business owners. For others, however, the opportunities had to be regulated. Especially in contracts regarding apprenticeships we can read about such secondary employment conditions. That of a boy who was to undergo a five-year training to become a weaver is exemplary. He had the following line in his contract, dated to the year 183 CE:

‘The boy shall have twenty holidays in the year on account of festivals without any deduction from his wages after the payment of wages begin’. (P.Oxy. 4 725)

In another contract dated to the end of the second century (P. Oxy. 14 1647), we find a comparable arrangement for an enslaved girl, allowing her eighteen days off for festivals.

Eighteen to twenty days off a year seems quite a generous amount, but of course the apprentices did not have the luxury of a weekend, or one fixed rest day every week – the week was in fact barely known in the Roman Empire at this date. These twenty days are marked for festivals, but since the festivals are not specified in the agreement, it looks like these apprentices were free to choose for themselves which festivals to participate in. We know from other sources that there were many more festive days than twenty in a year, so they still had to make a choice. Unfortunately, we have no information on the amount of feast days the weaver scheduled for himself.

A more complicated situation arises in an apprenticeship contract dated to 264CE:

‘And if the boy is idle on any days during the time that he is receiving wages, or (may it not happen) is ill, he shall stay with the overseer for the same number of days, working without wages. And the boy shall have, on account of festival holidays, Tybi, Pachon, the Amesysia seven days, at the Serapeia two days.’ (P. Oxy. 31 2586)

This unnamed boy gets days off for festivals as well, some of which are specified. The Amesysia was a weeklong festival for the goddess Isis, and the Serapeia were celebrated at the temple of the god Serapis. These festivals were apparently so popular at the time, that everyone was participating in them or at least was expected to participate. In another contract the Isis festival is specified as a reason for days off as well, underlining the popularity of this festival. There is, however, some debate on the interpretation of the days off in Tybi (27 December to 25 January) and Pachon (26 April to 25 May). As there are no festivals for Isis or Serapis during these months, some scholars suggested that this meant that the boy was free from work for the entirety of the two months. Because this seems excessive and would contribute to a significant increase in free days compared to our earlier sources, it appears more likely that the boy also receives seven unspecified free days in the months Tybi and Pachon, to be scheduled at will.

The total of free days then amounted to 23 days, which is more in line with the 18 and 20 days mentioned earlier.

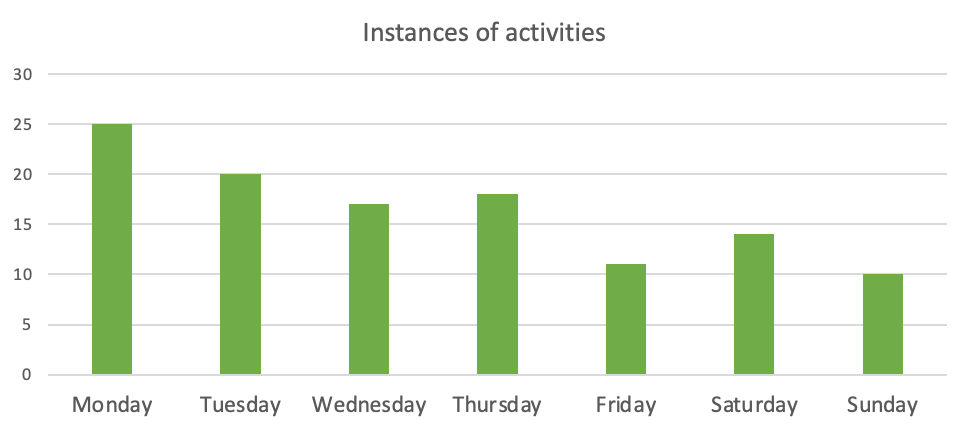

In a fourth-century monthly overview of provided camel transportation (CPR 19.66), the presumed owner of the camels kept a meticulous list of delivered goods per day and of the number of camels needed. On some days, he did not record any activity, but these days were ‘free’ (ἀργία). This could mean that there were simply no goods for him to transport or that he decided to take the day off. For instance in the month Tybi, he did not work on Tybi 6 (1 January, the Roman Kalends festival); Tybi 8 (3 January, still part of Kalends festival); Tybi 11 (6 January, the Christian feast of Epiphany, that emerged during the third and fourth centuries); Tybi 17 and Tybi 29. As the first three dates could be connected to a festival, it seems quite likely that at least some of his free days were spent celebrating a festival. Or that there was no work for him, because his clients were at a festival.

Unfortunately, not every month is included in this document, but based on the extant data, the days off would amount to roughly 40, which would be quite a high number just for festivals. It seems therefore safe to assume that the ἀργία-days of the camel owner included both festivals and days where business was slow, which could have overlapped.

This brief analysis shows that in all probability there was some room for individual choices regarding the participation in festivals in Roman Egypt. Celebrating a festival together will make people feel part of a community. But it could also lead to stricter boundaries between communities, if they celebrate different feasts at different times.

This Easter weekend, many people in the Netherlands will have come together with family or friends and perhaps enjoyed a special meal. As Easter is a fixed national holiday, not everyone will have deliberately chosen to celebrate the feast. But because it has been traditionally celebrated for years now, the festivities do contribute to our national festive rhythm, while in the meantime providing us with chocolate eggs.

Elsa Lucassen