Late antique Christians, and monks in particular, were supposed to “pray without ceasing” (1 Thess 5:17). But what did this mean in daily life? How many prayers were considered appropriate and what tools did monks have to keep track of their prayer count?

Early Christian church regulations, which are best preserved in Syriac but also partly attested in Coptic, instruct Christians to say the Lord’s prayer thrice a day (Didache 8.2; second century), and later, to observe six prayer times: before dawn, at dawn, in the morning, at noon, in the afternoon and in the evening (Apostolic Constitutions 8.34; fourth century).

John Cassian (d. 435), who temporarily lived as a hermit in Egypt as a youth, observed that monks across Egypt observed a fixed number of twelve prayers during the night and evening services, as early monastic leaders had established (Institutes 2.2.3-4; 420s). These prayer moments marked the start and end of a day respectively, and were prayed collectively or individually, in view of the fact that hermits in Nitria only met on Saturday and Sunday to attend mass (Lausiac History 7.5).

Pachomius (d. 346), founder of eleven monasteries in southern Egypt – for monks and nuns separately – compiled the first monastic precepts, which are known from Jerome’s Latin translation as ‘the Rule of Pachomius’ (385-420). These regulations make a distinction between communal prayers by the entire community at night, noon and in the evening (nos 20, 9+24, 121), and prayer in the houses in the afternoon, during which six prayers and six Psalms were to be recited (no 155) – twelve prayer units in total. Palladius (d. 431), who had also lived as a monk in Egypt, added that an angel instructed Pachomius to let the monks pray twelve units at night, twelve during the day, twelve at lamp lighting and three in the afternoon (Lausiac History 32.6; ca. 420).

In the two monasteries and one nunnery headed by Shenute (d. 451) near Sohag (southern Egypt) communal prayers took place before dawn, at noon and in the evening, and prayers in the houses in the morning and the afternoon. According to Shenute’s Canons, a prayer round consisted of six units (of a Psalm and a prayer?), and the prayer moments in the houses should normally last three rounds, but in Summer, when the hours were longer than during the rest of the year, monks and nuns had to pray four rounds (Canons 2.166-168). In the morning, four rounds were the norm, but five were prescribed when people woke up too early, and three when they overslept (Canons 2.169-172).

Anecdotes on hermits living in Scetis, Nitria and Kellia (northern Egypt; ca. 400) refer to daily private prayers, listing high numbers to impress and edify the audience. Moses, the penitent Ethiopian robber who became a highly respected hermit and priest, prayed 50 units, and Macarius of Alexandria and Evagrius both recited 100 units (Lausiac History 19.6, 20.3, 38.10). Paul of Pherme kept track of 300 units by putting 300 pebbles in his lap and dropping one each time he finished a prayer, until there were no pebbles left. Nevertheless, he felt inadequate upon hearing that a virgin in a certain village reached 700 units (Lausiac History 20.1-2; seven prayer moments of 100 units?). According to Macarius the Great, it was not necessary to make long prayers: ‘It is enough to stretch out one’s hands and say: “Lord, as you will, and as you know, have mercy”’ (Sayings of the Desert Fathers, Macarius the Great 19). These numbers came on top of the system of twelve prayers.

Later references to private prayer relate to seventh-century bishops with a monastic background in southern Egypt. After Basil requested Bishop Abraham of Hermonthis (d. 621) to ordain him deacon, he promised to perform one hundred prayer units daily (O. Crum 33). According to literary tradition, Bishop Pesynthios of Koptos (d. 631) used to pray 400 units at night plus an uncountable number of units by day, when he stayed in the desert in the neighboring district during the Sasanian occupation of Egypt (620s; Sahidic Encomium, ed. Budge, fol. 77a)

How did monks and pious Christians keep track of the number of their prayers, especially when they strived for 100 units or more? It is likely that they used prayer beads or prayer ropes (with 100 knots?), which they could easily take with them, but late antique examples have not been archaeologically attested. A quick search for prayer ropes leads to later Byzantine traditions that attribute their introduction to Anthony the Great (d. 356) or Pachomius, as well as to eighteenth-century Coptic icons that depict monastic saints holding a beaded string, and modern Coptic examples (fig. 1).

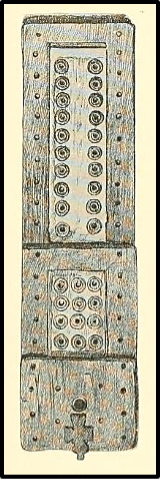

The only archaeologically attested object that was possibly used for counting prayers is a wooden box inlaid with bone, which displays regular rows of holes on three levels (83 holes in total) and contains smaller objects that can be used as dice (Louvre, E 21047; fig. 2). A small wooden cross used to be attached to the top of the box. Albert Gayet found the object in the tomb of Thaïas in Antinoopolis (Middle Egypt). The Christian woman was buried on a bed of palm branches, in a tunic with silk decoration and leather mules with gilding, while a fine muslin veil covered her face. The way she was buried suggests that she was a religious upper-class woman or even a martyr. Debunking the popular theory that she was the reformed courtesan Thaïs (fourth century), recent scholars dated Thaïas to the seventh century and identified her box as a game board. However, the fact that it was found upright between her folded hands, with the cross turned towards her – like rosaries in later Catholic burials – supports Gayet’s hypothesis that Thaïas used the object as a prayer marker (chaplet).

A later blog will examine the relation between prayer and work.