In the first months of my postdoc project, I have been entering information on dated Coptic texts in the Lived Time database, including deeds, tax receipts, letters and inscriptions. Sofie had already imported sources available at the papyrological platform Trismegistos.org, and I expanded the corpus with texts from less easily accessible publications or recent editions. Databases are wonderful tools for organising different kinds of information that are difficult to present in a clear overview in any other way. Normally, they can only display the data that has been entered, but what I appreciate about our database most is that it adds the day of the week, which offers the possibility of examining the working week of well-attested persons.

Such a study can only be successful, if the dates in the database are correct, and dating Coptic texts is a challenge: many documents, such as tax receipts, are not precisely dated, but refer to an indiction year (in a 15-year cycle which was used for taxation purposes), resulting in two or more options, e.g. 715 and 730 AD. Fortunately, researchers can propose specific dates by arranging such texts in a relative order on the basis of the persons involved, some of whom are also known from precisely dated deeds. In recent years, colleagues in Coptic papyrology checked and, where necessary, corrected many of the tax receipts published decades ago. As a result, it is possible to reconstruct to a certain degree the administrative apparatus of the town of Jeme, west of modern Luxor, from the 6th to the 8th centuries AD.

Sometimes, I need to correct the precise date given in older editions. About twenty years ago, colleagues became aware that the indiction year started four months earlier in Upper Egypt than was previously assumed: not on the first day of the Egyptian calendar (August 29), but around the first of May. Consequently, texts dated to May–August turn out to be a year older, and to have been written on a different weekday. In the case of single documents the difference is trivial, but when reconstructing the administrative network in Jeme and its development under Islamic rule, it is crucial that the dates are calculated correctly.

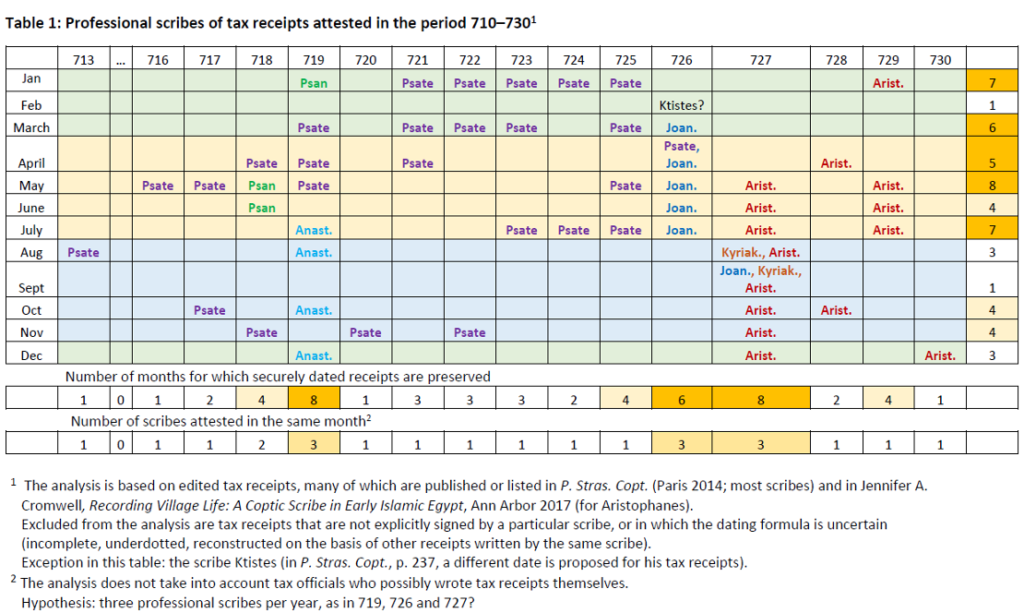

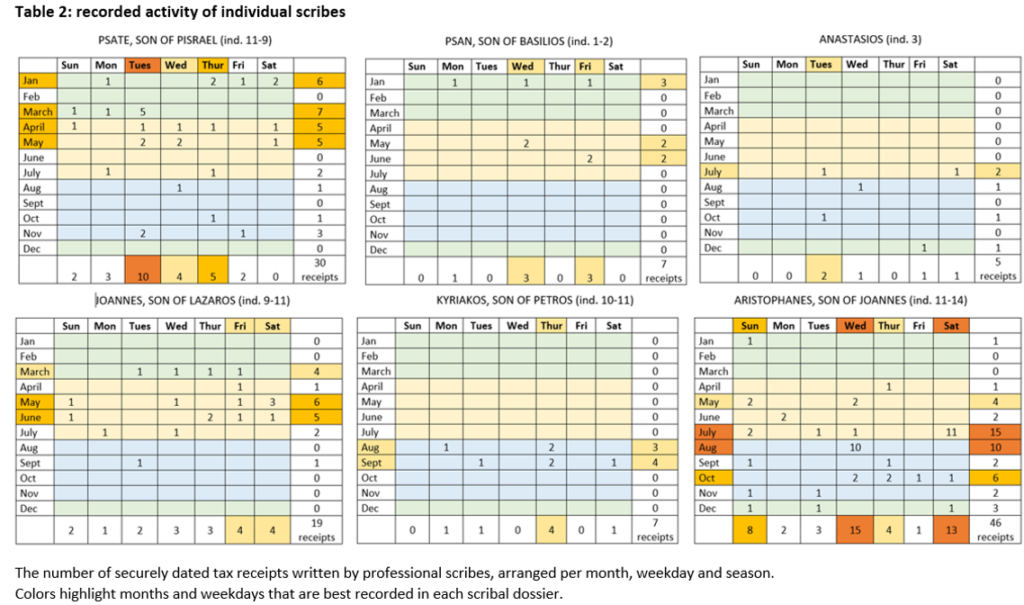

The tax receipts published so far were issued by village headmen in the period 710-730. Many of them refer to the poll tax, which non-Muslim (Christian) men had to pay to the Umayyad authorities. The scribes known by name included Psate, son of Pisrael (ca. 713-726), Psan, son of Basilios (717-719), Anastasios (719), Ktistes (726), Johannes, son of Lazaros (726-727), Kyriakos, son of Petros (727), and Aristophanes, son of Johannes (727-730). By exporting the dates of their receipts from the database to Excel, we can create tables that show to what extent their tenures overlapped (Table 1) and in which months, or on which weekdays, they were most active (Table 2).

Table 1 suggests that the tax administration intensified: Psate’s activity is spread over fourteen years, but he wrote most receipts during the winter (December–March) and harvest (April–July); Aristophanes was active for four years, but wrote more receipts, almost as much during the inundation (August–November) as during the harvest. Other scribes worked for increasingly shorter periods, ranging from two years according to the Julian calendar, but only during part of the year (Psan and Joannes), to a month (Ktistes, but his dossier is likely to be incomplete).

Table 2 seems to confirm the impression that tax-related scribal activity increased in Aristophanes’ days: whereas his earlier colleagues were most active during particular months and on specific weekdays, but hardly on Sunday (the Christian day of rest), Aristophanes was called upon during most of the year and every day of the week, including Sunday, which happened quite frequently. Friday, the day on which Muslims gather for prayer in the afternoon, appears to have been a fairly quiet day for most scribes. It would be interesting to know to what extent office days for Muslim officials influenced the workweek of the Christian scribes at Jeme, and whether they could choose their workdays.

Further research is necessary to explain these patterns. My analysis of scribal activity could be refined by adding more tax receipts, written by the above-mentioned scribes or less well-known ones, and the same method can be applied to the village authorities and tax collectors who issued and checked the receipts. Still, even in this very preliminary stage, it demonstrates the value of the database for reconstructing the administrative apparatus of Jeme, which in turn can lead to a more thorough study of the history of one of the best recorded towns in Egypt in the early Islamic period.

Renate Dekker

One Reply to “Blog: How the Lived Time Database Contributes to the Study of the Workweek of Scribes in Eight-Century Egypt”

Comments are closed.