The rhythm of our modern lives is set by the alternation of weekdays and weekend. This alternation between work and rest goes back to the early Jewish and Christian introductions of the Sabbath and the Sunday respectively as a weekly day of rest. This one day apart sets the pace of peoples’ lives. Jewish communities were – by far – the first to live according to a seven-day pace, but it was with the Christian day of rest that this lifestyle spread far and wide.

Although we can barely imagine life without these regular days of rest, the Christian Sunday was not introduced easily or quickly, even though the concept of a cycle of seven days was already known in the Roman Empire before Christianity. (For the planetary week, see the earlier blog by Elsa Lucassen.) In the early days of Christianity, when Christian communities were actively trying to distance themselves from their Jewish heritage, the Sunday was strictly a day of religious celebration, not one of rest. In 321, however, the Roman emperor Constantine decreed that all judges, artisans and people in the cities should abstain from work on the holy Sunday. The closing day of the court was quickly implemented, as attested in the proceedings of a low-profile court case in a provincial town in Egypt in 325. But the Roman authorities had little influence of the everyday lives of artisans and city-dwellers. The broad survey of precisely dated papyri in the Lived Time project shows exactly how little.

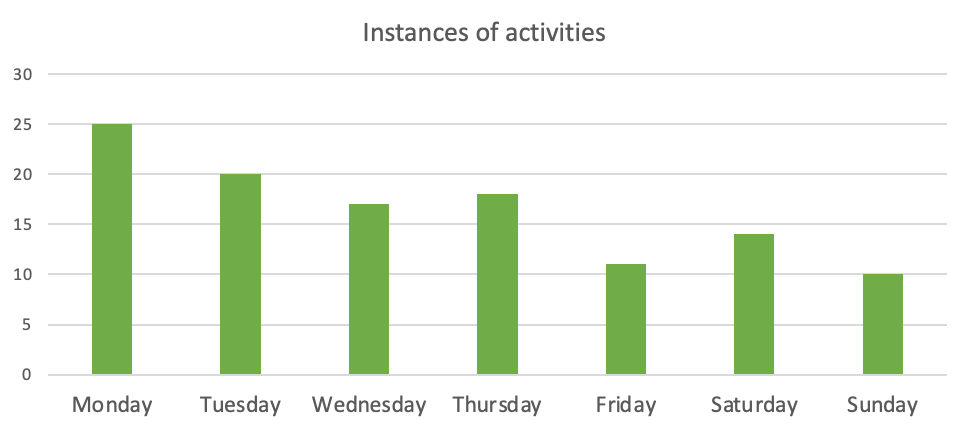

For our project, we look, among other things, at precisely dated activities in texts. Often the date of the activity is the same as that of the text, as the production of a text (e.g. a contract, an account, a meeting etc.) is a side-product of the activity. The temporal patterns in the production of texts therefore represent the temporal patterns of a broad spectrum of economic, administrative and social activities; and the patterns for specific types of texts reflect the rhythms of specific activities. If one would look at the temporal patterns in modern text production, one would see, a steep decline of work emails and bills in the weekend, but perhaps a rise of shopping receipts on Saturdays. In the documents written in fourth-century Egypt, we find no such pattern: people produced just as many documents (of the same variety of types) on Sundays as on other days of the week. This is similar in the fifth century, but starts to change in the sixth century, when the documentary record clearly drops on Sundays and peaks on Mondays.

To get a better sense at what was happening here, we can zoom in on the papyri of one town in Egypt, Aphrodito. The discovery of the enormous archive of the local big man Dioskoros, which relates to both his and his father’s personal administration as well as to the village more broadly, has made this small town in the sixth-century in the words of Giovanni Ruffini “the best document place per capita in the entire ancient world”. This archive suggests that every administrative office representing the Roman authorities was closed on Sundays. This is in line with Roman law, which had, since the first law by Constantine, added more and more aspects of government that were not allowed on Sunday, such as tax collection. Sermons by high profile clergymen show that the Church too promoted Sunday rest in the sixth century (see the SOLA database). This phenomenon is sometimes referred to as the ‘sabbatization’ of Sunday.

But the local population had clearly not yet interiorized this idea of obligatory rest. The pattern (somewhat fewer private documents than on other days, followed by a peak on Mondays) suggests they worked somewhat less on Sundays, but they were hardly restful. The most logical scenario is that on Sundays they spend a part of the day normally devoted to work to attending mass (a regular activity that did not produce texts, and is therefore much harder to locate in our evidence) and that they used this religious get-together also as a social occasion to arrange more complex business meetings on the following day, hence the peak on Monday. As major transactions generally involved a notary and witnesses acceptable to both parties, this kind of business could not be done on the spot.

Aphrodito is also the finding spot of another large archive, this time from the early eighth century. This second find creates the opportunity to see how the rhythm of village life had evolved in the intermediate 150 years, during which Egypt transformed from a Roman province to an integral part of a Muslim empire. The archive of Basilios, the local head of the administration who was in direct contact with the Arab governor in Fustat, contains little information about private activities, but an analysis of the temporal patterns shows clearly that he organized his administration in contrast to the rhythms set by Fustat. The governor sent him a never-ending stream of orders. Repeatedly, messengers arrived at his door on Sunday. This kind of demands on his time were outside his control. But every activity the Christian Basilios did have under control had to wait: he and his team stuck to their day of rest. This shows that under this new foreign domination, the observance of Sunday rest shifted from a norm set from above, but often ignored in private contexts, to a practice valued by the local population as a mark of their own Christian identity in a discourse of difference.

Sofie Remijsen

This blog is based on: Remijsen, S. (2022). Business as Usual? Sunday Activities in Aphrodito (Egypt, Sixth to Eighth Century). In U. Heil (Ed.), From Sun-Day to the Lord’s Day: The Cultural History of Sunday in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages, Turnhout, pp. 143-186.